Fear of nuclear war, herbal disasters, economic crisis? Survival Condo may be the answer

‘Mechanical level’, ‘medical level’, ‘tent level’, announces the voice when the elevator descends to the ground. He had entered the parking lot, in the most sensible part of the building. I through an inverted skyscraper, emerging the numbers of the ground, third, fourth, as we explore the depths of the building. A forced guy in his fifties, Larry Hall, ers up next to me, whistling, in a black blouse tucked into blue jeans.

When the doors open, I can’t suppress a laugh. Across from us, 4 floors below downtown Kansas, there’s a grocery store with shopping carts, blood-free closets and a coffee device over the counter. Hall smiled.

“That’s good, is it rarely like that? In the original renewal plan, it is only said ” reservations “at this level. The psychologist we hired for the task took a look at this and said, “No, no, no, it’ll have to look like a Whole Foods miniature supermarket. We want a tile floor and boxes superbly presented, because if other people are locked in that silo and have to come here and rummage through cardboard boxes to get their food, they will have depressed other people everywhere. “”

I’m an intern in the world’s most sumptuous and complicated personal bunker: the Survival Condo. It was once a U.S. government missile silo. From the Cold War. Built in the early 1960s, with a charge of approximately $15 million to the U.S. taxpayer, it is one of 72 structures built to protect a nuclear warhead one hundred times more resilient than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Many of those silos were destroyed and buried after decades of unused use. But not all of them.

A silo in Wamego, Kansas, was raided by police in 2000 when they discovered a giant LSD production facility inside, producing up to a third of the country’s supply. Another silo near Roswell, New Mexico, had been remodeled into an extraterrestrial communication facility that transmitted a binary code through a laser beam into the cosmos. A third silo was funded through William Shatner (also known as Captain James T Kirk of Star Trek) to an advertising research center to examine the productivity of Mars colonization. However, another silo, in Abilene, Texas, is now an educational dive center.

Of all the projects that have flourished in the deserted spaces of the state, Hall’s is perhaps the most impressive. As a former government entrepreneur, real estate developer and apocalyptic preparer with a master’s degree in business, he had the best combination of attriyetes to build what had ever been done before. In the 1990s, he had worked for a self-defense contractor, designing the weapons knowledge base for an Air Force surveillance aircraft. Later, he began building strengthened knowledge centers. At first, he planned to build one in a silo; however, he soon learned that there is another emerging market, in apocalyptic preparation for the super-rich.

Hall bought the $15 million silo in 2008 for $300,000. In 2010, he remodeled the 60-meter-deep construction on a 15-story luxury asshole, where up to another 75 people can only five years inside the sealed, self-contained bunker.

Hall knew there would be takers. I had heard of Silicon Valley elites burying bunkers on ranches in New Zealand, wealthy Russian oligarchs buying entire Pacific islands to escape and bunkers outsourced through the rich (notable examples come with Bill Gates and Kim Kardashian). According to a 2007 Wired mag article, Tom Cruise planned to pay $10 million to build a bunker under his 298-acre property in Telluride, Colorado. In Los Angeles, a pornography production studio even to build its new headquarters in an underground bomb shelter, you know, just in case.

In the spring of 2020, public frustration with police brutality sparked civil unrest in U.S. cities, adding Washington DC. At one point, President Trump hid in a bunker under the White House when protesters clashed with police and secret service agents abroad. In addition to bunkers related to the president’s office, Trump boasted of having bunkers beneath his New York property, his golf course in Palm Beach and the Nearthrough beach resort, Mar-a-Lago. The latter is supported through a bunker built in the early 1950s through the person rich in breakfast cereal Marjorie Merriweather Post. In 2007, Trump told an Esquire reporter that he had spent $100,000 to “repair” the golf course bunker and that, in the event of a calamity, the Mar-a-Lago shelter is where he sought to be.

Lavish bunkers such as these are built not so much in response to a single imminent catastrophe, but out of a more general disquiet about a variety of threats. Preppers dread nuclear war and accidents, a collapsing ecosystem, runaway technology, pandemics, natural disasters, economic meltdown and violence.

Waiting for those mistakes can take a few years. It’s not so hard to believe living underground for a short-term lockdown. Another challenge is to create a psychologically tolerable long-term environment, so as not to overemphasize the issue, so that members of this newly troglodytic network do not homify from each other.

***

At the beginning of the Cold War, governments, the military, and universities conducted experiments to see how long other people could resist getting caught up in an underground combination. In total, in the early 1960s, another 7,000 people volunteered to be locked in spaces with teams ranging from the length of the family circle to more than 1,000 as a component of U.S. government attempts. To assess the mental impact.

In a study at the University of Georgia, researchers locked up teams of men, women and young people between the ages of 3 and 70 in protective shelters six times between 1962 and 1964 during varying periods, which had to feed on bulgur and water biscuits. They had no bathing water, no bunk beds, no blankets. Researchers “found that no harmful mental or social effects occur during periods of two-week organizational confinement under austere conditions.”

It seemed that other people could simply adapt, as long as they knew the stage was temporary. The review advised that when citizens wanted to shrink, the required preparation was less vital than the desire to “prepare them for a quick adjustment to the post-attack global emergency.”

Another report, published through the U.S. National Science Foundation. In 1960, he reported that the time extended underground “can lead to many physiological deprivations,” adding “difficulties in concentration, irritability, depression and personality disorders.” In other words, other people can survive, but they wouldn’t succeed. It would only be a matter of time before anxiety, and worse, began to overwhelm the group.

Hall, however, believes that he has discovered a solution to these potential obstacles. The key to underground well-being, he tells me, may be to create a ghost of life in general. “So let’s ask other people to make bread and coffee, other people can promote their yoga elegance on the coffee slate, and we’re going to stack this case of sausages with 3 other species of tilapia that are grown in the nearby aquaponics facility.” Nitrates from fish faeces will fertilize the soil for plants at the FDA-certified aquaponics facility. Fresh produce here will end up in the general store. Remains of plant matter, heads and bones of fish will be subjected to a grinder to become food for residents’ dogs and cats, adding Lollipop, Hall’s cat, which fortunately walks in the four-story silo above us. “It’s imperative that we inspire other people to come and shop and be sociable,” Hall says, “because obviously everything here is already paid for.”

Money, in other words, will be priceless in the Survival Condo, which is just as good, given the charges that induce bankruptcy to buy there in the first place. The half-floor apartments here charge $1.5 million (1.2 million pounds); half-story apartments $3 million (2.4 million pounds); and a 3600-square-foot two-tier penthouse sold for $4.5 million (3.6 million pounds). A total of 57 other people will live in 12 apartments, paying another $5,000 (4,000 euros) according to the month in the rates of the residents. An apartment, purchased in cash, is designed to look like a log cabin, with a loft neglecting a fake home flanked through a six-screen demonstration of a snow-covered mountain range.

None of those who buy the bunker are at the time of my visit. Apart from me, Hall, Lollipop and the maintenance manager on site, there is no one inside. Unsurprisingly, citizens are evasive and narrow-minded. One is Tyler Allen, a genuine florida real estate developer. Another is Nik Halik of Melbourne, a “passionate” adventurer and wealth strata, who flew in a civilian project to the area and immersed himself in the remains of the RMS Titanic.

***

For much of my life, the word “bunker” evoked the intellectual symbol of a ruined concrete monolith of World War II, a housemate on a beach, collapsed in the sand, covered in graffiti. There is no doubt that during the twentieth century, the bunker became a form of ubiquitous architecture in reaction to the risk of air power. However, it has deep roots in human history. In Cappadocia, in the central Anatolian region of present-day Turkey, there are 22 known underground cities on a large scale, excavated around 1200 BC. Many still exist. Archaeologists say Derinkuyu, the innermost of the 22, reaches 60 meters below the surface and housed up to 20,000 people, as well as its livestock and food stores. It consisted of more than 18 floors of rooms, halls, churches, armories, garage rooms, wells and bathrooms.

In recent years, bunkers have not only spaces for human bodies, but also a position to revive the things that matter to us. The Library of Congress, for example, adapted a massive bunker in Virginia and filled it with its collections of movies, television and sounds. The goal is to avoid some other horrible loss such as exposure to fire at the Great Library of Alexandria 2000 years ago.

At point 11 of the Survival Condo, about 50 meters underground, Hall and I stop at a 1,800-square-foot house. I had the same feeling as walking into a room at a chain of hotels. The apartment never used. It features a carpet posted in Navajo, a comfortable white sofa and a stone electric home with a flat-screen TV. A marble countertop extends to a bar that separates the living room from the kitchen, which is filled with high-end appliances. I take a look at one of the windows and I’m surprised to see that outside it’s dark. My instant physiological reaction is to assume that we had to be underground for longer than I thought. Then I realize my mistake.

“Got you,” Hall says, laughing. He picks up a remote control and flicks on a video feed being piped into the “window”, a vertically installed LED screen. The scene depicted is the view from the front, at the surface-level entrance of the condo. It is daytime, breezy and green outside. I can see my car through the branches of an oak tree, exactly where I’d parked it a few hours earlier. But when this video was made is not necessarily obvious – maybe there is a time lapse and I am watching a prerecorded past I am convinced is the present. The thought sends a prickle of unease down my spine.

After the lock, Hall can decide exactly which device is due percentage with the other occupants. His sense of context, of reality, of what happens on the floor, whether the global is over or not, is entirely in his hands. “Most people prefer to know what time it is than to see a beach in San Francisco,” he says casually, reliving again. The screen is empty.

Hall not only experiments with new technologies; think about how people think and react. I know he was once a “ghost” and he worked as a government contractor. I wonder if all this was funded through the Department of Defense as a human Petri dish, the next iteration of the Cold War human reports of the 1960s. Not telling the population that they are participating in an experiment would be the key to their rigor.

But Hall explains that he lived in the bunker for a month before the installation of the “window system”. It’s Array, he says, like living in a casino. Unable to verify that the passage of time correlated with what his watches told him, or with whom he was leaving or out of the bunker, he felt completely isolated. LED displays have replaced all of that, reintroducing a circadian rhythm.

One of the citizens of Survival Condo, the one with the two-story “penthouse,” embraced this idea. She filmed Central Park from her Manhattan loft, all 4 seasons, day and night, with the cacophonous sounds of urban life. To accommodate this year-round video hard drive, Hall and the maintenance technician knocked down the cement wall of the silo and covered it with reflective paint. Then they built a balcony with a railing and, using a $75,000 projection projector (60,000 euros), gave the impression that the resident can simply walk down the balcony to look at the city through sliding glass doors.

“The psychologist explained to me that my task is to make this position as general as possible,” Hall says. “No one needs to be reminded all the time you basically live on a submarine. Come on, I’ll show you the survival system.”

We take the elevator to the mechanical level, just below the surface, where Hall points me towards an opposite osmosis filtration system. Water is pumped from forty-five underground geothermal wells a hundred meters deep. Ten thousand gallons of water can be filtered according to the day in 3 electronically controlled tanks, containing 25,000 gallons.

We move on to point 3, where Hall enters a code into a thick metal door. He opens it to reveal something similar to the Scene of The Matrix in which Neo and Trinity take the unlimited arsenal to their passods. “It’s one of the 3 arsenals,” Hall proudly announces. “In each of them, we have precision rifles, AR, helmets, fuel masks, first aid kits and non-lethal pistols like military-grade pepper spray.”

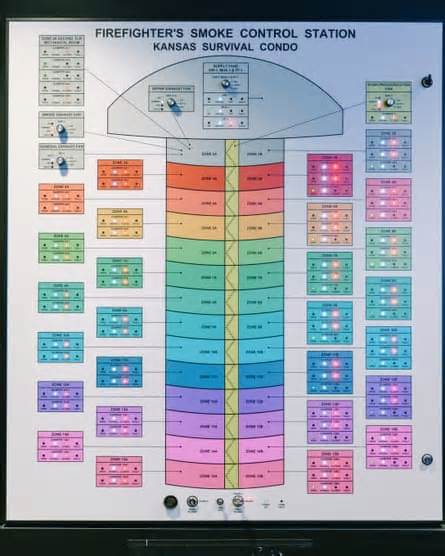

But, he continues, “arsenals may not even be necessary. Outside is a remotely controlled Array223 rifle. You can kill other people like a video game. Hall opens another bulletproof door with key code to reveal a huge screen bank and a control panel with a joystick. Explains that, they have internal and outdoor full-spectrum and thermal, nighttime and full-spectrum cameras throughout the facility, the rifle can be put into automated defense mode by firing three-shot bursts over anything in your watch box.

“We can also hit them with bursts of 3 paintballs,” he said. “It will let us know what’s next, if they keep moving towards the condo.”

The joystick is part of a larger multiscreen control panel called Kaleidoscope, a basic AI system capable of closing off parts of the bunker automatically in the event of, say, a fire. If that puts you in mind of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the possibility that Kaleidoscope could start trapping people and hitting them with three-round bursts, you’re right in sync with me at this point.

Hall stops and takes a deep breath. “Listen, ” he said, “the fact is that it’s not an area of hope. The defensive capability of this design existed only to the extent that it was mandatory to protect a missile. This bunker is a weapons system. We’ve turned a weapon of mass destruction in reverse. It’s a safe, autonomous and sustainable architectural experience: it’s an underground equivalent of the University of Arizona Biosphere project.”

The project, better known as Biosphere 2 (because Biosphere 1 is Earth), was an environmental sustainability experiment and one of the most ambitious network isolation projects ever orchestrated. In 1991, in Oracle, Arizona, a team of 8 – 4 men and 4 women – locked themselves inside a glass dome to see if they could be in a closed formula for two years. The experiment, which took up a three-acre complex in seven “biomes” beneath the glass, was successful, but plagued by the social department and low oxygen levels that led to excessive fatigue and even banana theft, after disappointing biome yields. . leads to rationing. Sounds fun until you think the food disappears while you’re locked up in a building with hungry people.

Biosphere 2 has taught us a lot about how humans act under excessive pressure. Paradoxically, for an ecological sustainability project, it was financed with oil money. He also resumed the project before the time through Steve Bannon, Trump’s leading former strateeist, who took a copy of The Fourth Turning, William Strauss’s e-book and Neil Howe about the apocalyptic renaissance.

I realize that Biosphere 2 and Hall Silo can mark a turning point in the history of architecture. Both are outliers that point to the “normalization” of the bunker experience. Rather than just for any apocalypse, those technologies and the social systems needed to keep them in full development are being tested and changed long before they are needed.

Our tour continues. As a strong Willy Wonka, Hall takes me beyond the climbing wall, air hockey and table tennis, and a puppy park with synthetic turf nestled between a fake tree and a sunny mural in the Rocky Mountains. Open a door and activate a transfer to eliminate the darkness of a 50,000-gallon metal pool flanked by a waterfall of rocks, sun loungers and a picnic table. A mural of a tropical beach is painted on the wall.

We go back to the elevator and press the movie button. “Down,” the elevator said, taking us about two hundred feet below the Earth’s surface in 20 seconds, passing a dozen condos along the way, adding Hall at point five.

The cinema is on the penultimate level, sitting on water pumps and storage. It features leather reclining chairs on the terrace in front of a giant screen. We set up and lifted our legs while Hall opens the opening credits of Skyfall, his favorite in the 007 franchise. Scream on the soundtrack that we are immersed in 7.4 THX surround sound and 4K video projection. After a few minutes, Hall introduces me to the adjacent bar on the subject of airplanes. One of the citizens donated 2,600 bottles of wine from his place to eat to buy it.

Leaning on the bar, Hall explains that the psychologist he hired also worked on Biosphere 2. “He checked every single detail. From acoustics to textures and colors of walls. Even the LED lighting fixtures in the bunker are set to 3000 Kelvin [a hot white] for depression. People want to know why citizens want all this “luxury,” but what they don’t get is that it’s not luxury. This is the key to survival. If you don’t if you have any of this, you will start to have varying degrees of depression or cabin fever.”

Hall develops his theme. “In fact, everyone wants to work, in general. Holiday people are leaving destructive trends. It’s just human nature. You have to have a minimum of four hours of work and rotate jobs so that other people don’t get bored and break things.” he says.

In the construction of these spaces, we implicitly assume that we have given up repairing the global that we have broken. You may believe that the resources invested in the construction of these underground redoubts can be better used to control the catalysts of the disaster. But that’s why we have to pay attention to personal bunkers: they reflect how much our concern has saturated us.

When the tour ends, we go back to the surface. After only a few hours in this hermetically enclosed environment, the warm sun on my face and the smell of trees and grass give me an impossible feeling of resisting having entered an animated portrait through a mysterious force.

***

I started writing this delight when I was in Sydney, Australia. When I left, the country was in the midst of catastrophic wildfires. A billion animals were burned alive. In January 2020, the western Sydney suburb of Penrith reached 48.9 degrees Celsius, making it the position on the plane. When I returned home to California, the plane descended into a haze of smoke emanating from the wildfires surrounding Los Angeles, erasing the distance across the Pacific. I came here with my spouse to take care of my mother, who needed spinal surgery. My mother was sent back in a hurry just as the Covid-19 pandemic was beginning to spread in the United States. When we lifted her out of the wheelchair to the car, tents were erected behind us in the parking lot of to Torrance Memorial Hospital for the expected patient overflow. We both ended up in our L.A. bunker for months. As the virus spread, lines of origin, foreign travel and industrial routes, economic systems and social norms collapsed within weeks. The pandemic was exactly the kind of failure for which fault preparers were preparing.

Bradley Garrett’s bunker is published via Allen Lane on August 4 at £20. To order one for 17.40 euros, go to guardianbookshop.com. Bradley Garrett and Robert Macfarlane will discuss Bunker on a virtual occasion for 5×15 on August 12.