If the final results of the presidential election remain dubious during a prolonged era, what will be their effect on the stock market?

The Economist is nervous.

The Financial Times predicts “havoc” and warns that “the stability on which markets are located is threatened. “

Technicians point to dizzying trends in recent market volatility, pointing to the “worst chance in history. “

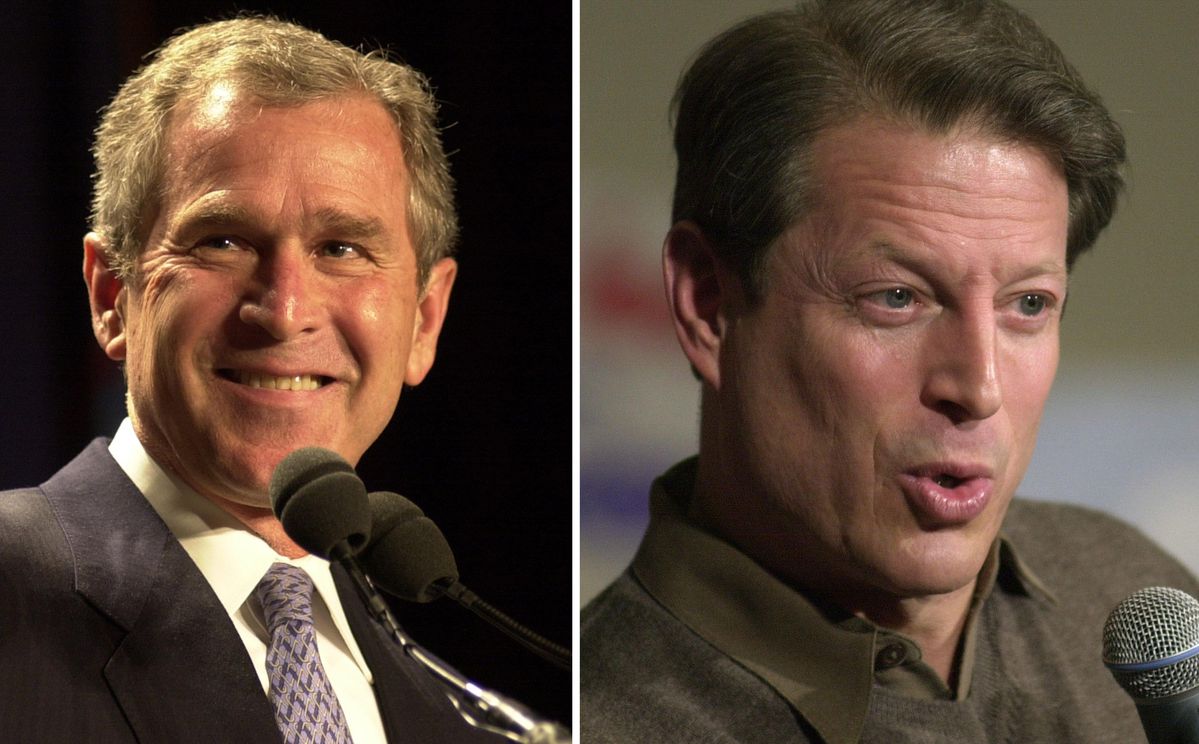

And everyone remembers (or thinks they remember) how the market completely collapsed bush’s episode against Gore in 2000.

Or did you?

Let’s take a first look at the 2000 case.

The 2000 presidential election was held through 537 votes in Florida (out of a total of one hundred million votes in the United States). The result, of course, was discussed. The recounts were ordered, debated, disputed, interrupted, resumed, questioned. The case went to court, prolonging uncertainty for 35 days until the Supreme Court declared George W victorious. Bush, it’s been a time of electoral chaos like no other since the 19th century.

The Economist would like the uncertainty to have failed the market.

But is that an adequate description of what happened?

In the week that included the 2000 elections, the time when uncertainty was injected into the monetary formula, the market place fell by 4. 3%. formula — also saw the market spot fall by 4. 9%.

The monetary context was broader: inventory costs were already falling to the first level of a massive bearish market cycle, which began in the summer of 2000 and continued for another two years. The S

In fact, the four weeks between the end of election week (when the wonder or surprise thing had been absorbed by the market) and the court ruling, four weeks in which the thing was not resolved, the occasions were quite confusing, and possibly the uncertainty was the highest: inventory costs really increased.

In other words, for more than a month, while the political procedure went through a series of tortuous and unprecedented manoeuvres in the component of all components: recounts, contested votes, prosecutions, judicial mandates, warnings, judicial decisions, judicial decisions, media frenzy. the inventory market turns out to have been . . . Imperturbable. No s collapse. Don’t panic.

Therefore, the market context is important. The Bush v case. Gore does not really include the concept that market locations are inevitably disturbed by this kind of electoral uncertainty. Markets evolve in reaction to “events” (news, surprises, shocks), but are also driven by broader monetary and economic trends. In the 2008 elections, for example, the market site fell by 11. 6% within 35 days of the election. It would obviously be wrong to interpret this sharp fall as a symptom of electoral uncertainty: there was none in 2008. the giant fall in percentage costs from September 2008 to March 2009.

A month ago, the currency headlines were on fire: the US election rated the worst threat in the history of VIX futures.

(Worst of the story! I’m sure what it means to “flee to date to an express tenor”, but you get the idea. A scream is a scream).

So what is VIX and why do we think it anticipates disruption when it rises? (The following is a simplified description).

The VIX is an index that measures the volatility of the place at the place of the stock market. The higher the volatility, the higher its “value”. As volatility and VIX increase when stocks fall, the acquisition of VIX-based monetary tools is considered an effective policy, a type of insurance – as opposed to a market slowdown at the place of acceptance. That’s why investors have paid so much attention to VIX and derivatives. In particular, The Economist cites VIX Futures securities as a sign of expected misery of the market site over the next period. Bloomberg’s analyst is, for him, a decisive sign of an imminent “risk of occasion,” and the occasion in question is interpreted as the prospect of chaos in the upcoming presidential election.

One way to query this metric is to read about the “time structure” of VIX futures contracts over the coming months. The graph below shows the values, as of September 29 of this year, of THE VIX futures that expire in 1 month, 2 months, and so on – up to five months (February). A giant premium – 10% – is interpreted as being paid for increased coverage of the problem in November and December. In fact, there is a significant value premium for futures contracts until the middle of next year’s first quarter. This increased demand for “insurance” is interpreted as a sign of investor fear about the choice of a challenged or dubious election result in November/December and beyond.

But this would possibly give the wrong picture of the stability of those expectations. After all, volatility is . . . good, volatile. This year, the VIX was very nervous. In March, it reached an all-time high of 85 because the Covid crisis affected markets. More recently, it has recovered in reaction to “shocks”, some of which are obviously political in nature.

In any case, just a few days after the structure of this chart, THE costs of VIX Futures began to fall.

It is not far-fetched to read the VIX, and perhaps especially the long-term VIX covering the era of the next election (November/December), as a measure of political anxiety, but does it have predictive value?The VIX itself has now returned to its long-term average of around 21-22 (it is quoted in recent days at around 25). VIX long running has also declined and returned to August levels. We could conclude that the market is now “betting on less chaos than more” (as a clumsy article in The Economist concludes). Or maybe it just adapted to the new information momentarily stressful.

Past political occasions have led to short-term spikes in VIX and futures values. In 2016, November’s VIX futures rose 55 percent in three hours on election night when he began to feel surprised by Trump’s unforeseen victory. But until noon the next day, the value had returned to its point 24 hours earlier.

The key query is again: context. Is an increase in VIX futures a valid predictor of some kind of near-normal political distress or is it an adrenaline rush of worry or surprise, which decreases as the formula adapts to new information?

Or is it also, to some extent, a grass of the “democratic cycle” to which the authors of The Economist’s article refer?

I discovered a study originally published through the National Bureau of Economic Research that proved the dating between election cycles and the values of sales options. Selling characteristics are another way to protect yourself or protect against the threat of the problem in the stock market, and probably to stick to the same feelings that calculate the value of VIX futures. In examining 271 democratic elections in 20 countries, researchers discovered a persistent and significant value premium for characteristics that overlap with the era of national elections. higher value premium, suggesting that investors covered the so-called “extreme threat” (the probability of extreme, unusual or unforeseen results). In other words, it turns out that investors routinely buy insurance at the time of the election.

Therefore, the informational content of those metrics (VIX futures, promotional features) would possibly reflect a confluence of several streams of investor sentiment:

One last comment on all this: as noted in the previous column, markets are being silenced and the meanings of signals emanating from monetary tools are changing. This is true for recent monetary innovations, such as the VIX. VIX has been a marketable product for only about 15 years, and its rise to the market is a phenomenon of the post-2008 period. Uses related to the volatility of monetary tools have evolved and chances are that the “meaning” of the VIX and its predictive price today is not the same as it was a few years ago. Coverage concepts and techniques are also evolving. It is an exaggeration to say that investors have “played” the elections of, say, 1992 or 2000 in the same way that they can play the 2020 election.

It makes sense to think that uncertainty, whatever it is, will have to be bad for the stock market, but as I said in my previous article, common sense and market realities do not coincide.

George Calhoun’s new ebook is Price

My first career: I spent 25 years in the high-tech wireless industry, concerned about the progression and commercialization of the virtual generation.

My first career: I spent 25 years in the high-tech segment of the wireless generation industry, concerned about the progression and advertising of virtual wireless architectures (2G, 3G, etc. ). I was president of a joint engineering company with the complex. I was CEO and president of Illinois Superconductor Corporation, then head of investment corporation Elliott Associates. I have been chairman of the audit committee of several state-owned enterprises and have wide ranged capital raising projects, adding public offerings and personal financing. I have conducted due diligence technical and advertising tests on a variety of investments for several giant corporations of coverage budget and personal equity.

***

My current career: in 2003, I joined the Stevens Institute of Technology, where I created and oversaw a number of systems in quantitative finance and similar fields. I’m the Executive Director of the Hanlon Financial Systems Research Center at Stevens. -Principal investigator for a recent grant to develop National Science Foundation plans to create a cooperative center for university/industrial studies oriented to monetary science and generation. I’m from several e-books about wireless generation and my new eBook is Price

***

I can be contacted by email at gcalhoun@stevens. edu.