Advertising

Supported by

Times Insider

After patients sent us copies of their medical bills, I saw a trend that required further examination.

By Sarah Kliff

Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and offers a behind-the-scenes look at how our journalism is.

In recent months, I’ve spent my mornings with the same routine: reviewing the medical expenses of New York Times readers having coffee.

The documents are part of a task I started in August, asking readers to send the rates they faced for the detection and remedy of coronaviruses. Bills can reveal vital data that hospitals and doctors remain secret, such as the actual charge of a hospital. the amount of fees that go from one patient to another. A few drops for both days and two days, and I look at both of them.

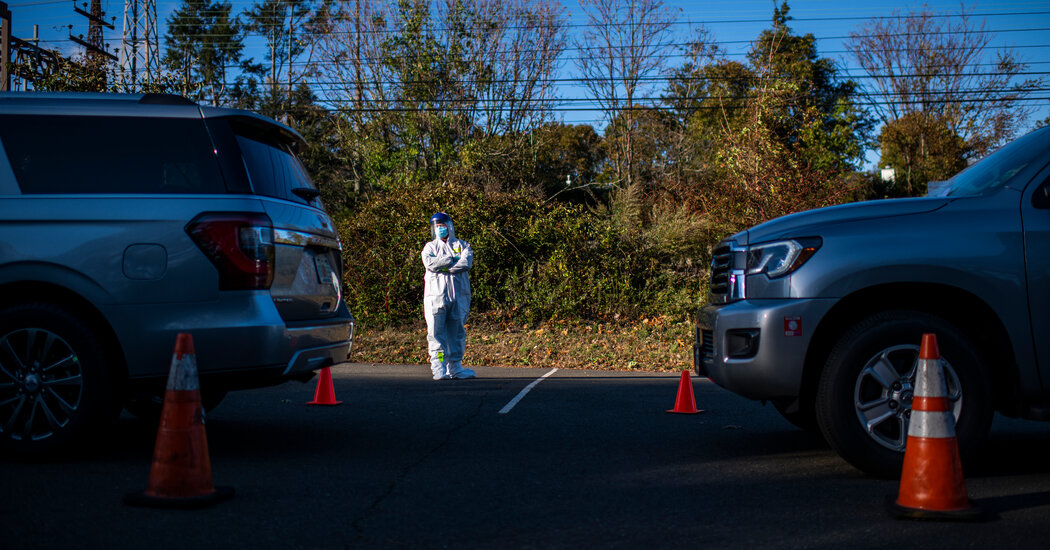

If you read enough, I’m at 400 and I’m counting right now, they can also show trends in how providers rate patients. That’s how I got here to my latest story, which is a doctor founded in Greenwich, Connecticut, named Steven Murphy: Patients say he used public testing sites to perform and beloved tests. Murphy defended his billing practices and said he provided important service to the community.

The story only caught my attention because of the large number of patients sending bills from their check sites in the northern suburbs of New York. Without this wave of reader presentations, I would never have known anything bad.

The first invoice with this carrier sent me on August 3, the same day I started the collection project. An outdoor New York City woman said she was “surprised” to see that a coronavirus verification site rated her insurance $1,944. Can this provider charge $480 for a 3-minute phone call giving verification results?asked in his presentation.

The next day, another presentation of a dr. Murphy’s patient arrived. “I can pay my bill, but I’m amazed at the charge the provider charges for the test,” the patient wrote. Four days later, another patient reported the “exorbitant rates” he faces, also from Dr. Murphy.

When the first bill came in for I, it was interesting, but I didn’t see the full story. Maximum fees for patients can simply be an anomaly. By the end of the summer, I had six separate expenses and a concept that something was wrong. Gradually he had accumulated a set of knowledge showing that a doctor who took care of public testing sites continually billed insurers more than $1,000 for coronavirus testing.

These are data that the most demanding pressure groups seek to keep secret. The American Hospital Association recently sued Trump management for new regulations that would make fitness service charges public (they lost that challenge, but said they planned to appeal to a higher court). makes it frustrating for hounds and patients to answer potential fundamental questions, such as the charge of coronavirus control in the United States.

Patients who went to one of these management control sites did not have a chance to know in advance the costs they would face. However, your bills can reduce the problem. They disclose secret costs with the naked eye.

They also involve five-digit billing codes, which I had to read more as I covered the physical care system. These codes involve precisely what service the doctor provided. In this case, these codes let me know that Dr. Murphy was not only charged for coronavirus tests, as his patients thought, and also charged another 20 respiratory pathogens.

Invoices are important, but they never make up the total story. After accumulating enough bills to start seeing a model, I started asking patients about their experiences. I talked to Dr. Murphy about his billing practices. He said the use of a broader proper verification because it may run into a wider diversity of diseases, especially for those that were symptomatic.

I spoke to medical billing experts to get their ideas and elected officials who had established verification sites. I filed requests for public records and, when they returned, I reviewed thousands of pages of emails between Dr. Murphy and city officials.

In maximum cases, the costs of the patients I obtain do not become stories, some do not reveal new information. Among those who do, we don’t have enough presentations to show a style or the ability to take a look at each of them.

In this case, however, we were lucky: a critical mass of readers made the decision to take a few minutes to send us a medical bill that she found strange, her decisions allowed me to do more of my homework and tell a story that could in a different way has remained unknown.

Advertising