The Takeaway is the national data program that provides the news and research you need. The program invites listeners to learn more and participate in American verbal exchange on the air and online.

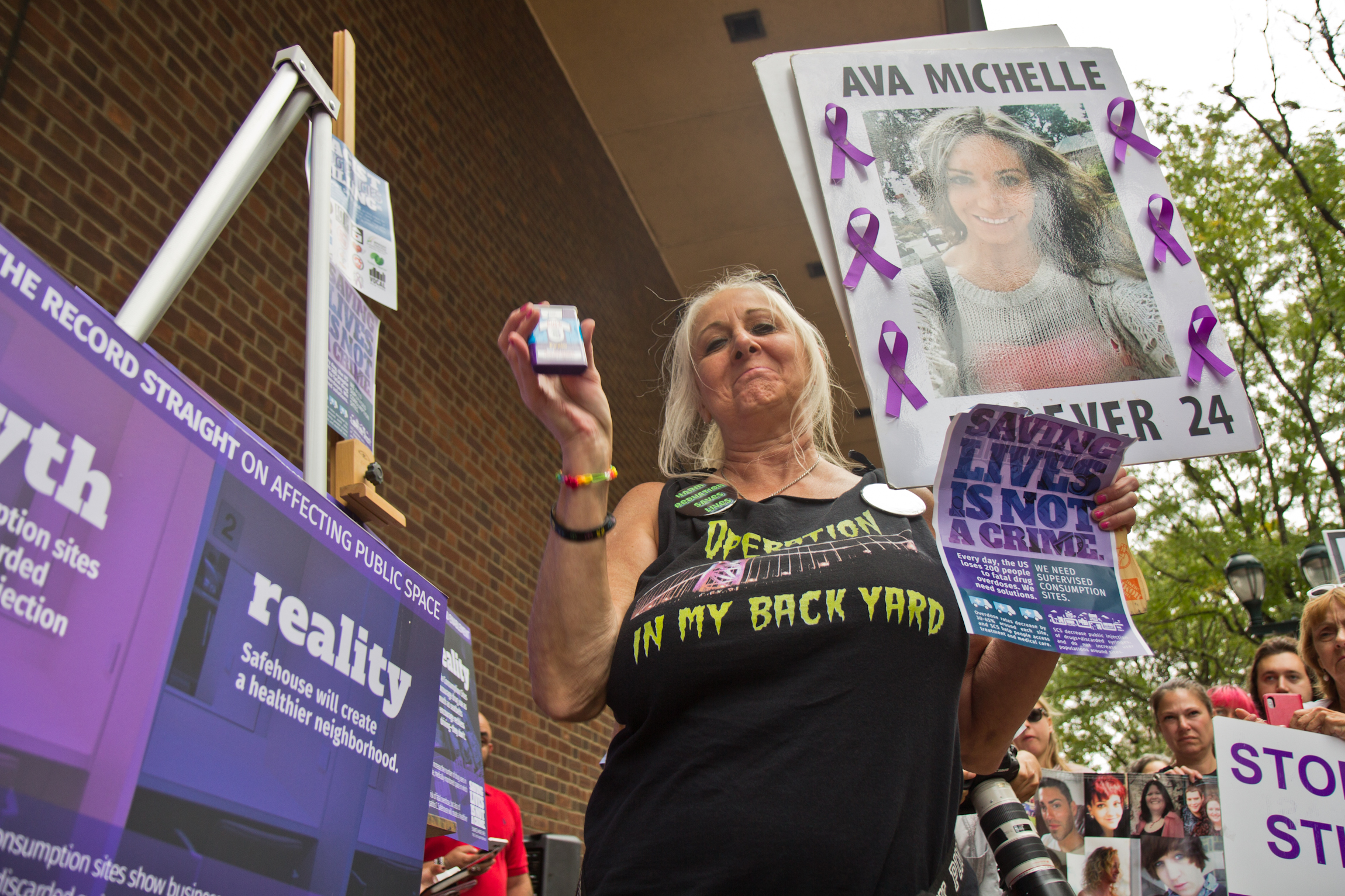

Deborah Howland, photographed in September 2019, her daughter on opioids in May 2018 (Kimberly Paynter / WHYY)

Eight months ago, the citizens of Philadelphia filled the city hall chambers to the gills to make their voices heard on the controversy of the day: Should Philadelphia be the nation’s first supervised injection site?

A few days later, as the risks of COVID-19 developed, the screams and shoulder-to-shoulder action at City Hall seemed extraordinarily ill-advised, and the opioid epidemic was temporarily eclipsed through the coronavirus pandemic as the ultimate urgency. crisis of our time. The Safehouse controversy has moved to the back of Philadelphia’s public consciousness: it looked like there were bigger fish to fry.

Now, two pandemic peaks and a capital election later, Safehouse’s arguments resurface, this time before the US Circuit Court of Appeals. But it’s not the first time

On Monday, Justice Department attorneys will argue that an establishment like safehouse needs to open, where other people can simply bring in illicit drugs and inject them under medical supervision to prevent an overdose, would violate federal law.

In a resolution that could pave the way for the first supervised injection site in the United States, a ruling ruled that Safehouse’s plan would not violate the Controlled Substances Act.

They made the same argument in October 2019 before federal district judge Gerald McHugh, who ruled that such a site would not violate the Controlled Substances Act. any of the retention area for the target of a controlled substance.

The resolution involved whether Safehouse’s explicit goal was to facilitate drug use or whether it was used as a means to an end, which in the end intended to help others with addictions and save lives.

McHugh felt that allowing the use of some drugs as a component of an anti-drug effort was not enough to make Safehouse illegal. “The ultimate purpose of Safehouse’s proposed operation is to reduce drug use, not facilitate it, and [the statute] does not prohibit the proposed conduct through Safehouse. “

U. S. Attorney William McSwain, who in rare cases has argued the case in person, promised to appeal immediately, Safehouse lawyer Ilana Eisenstein said at the time that she was convinced that her case would resist an appeal.

“According to my reading of the court’s opinion, there are many facts in dispute,” Eisenstein said.

Research suggests that supervised injection sites cause opioid overdose deaths and injectable drug infections.

A few months after its favorable court decision, Safehouse Control announced its goal of opening its first supervised injection in South Philadelphia.

The ad was wonderful for two reasons: first, its location. Most people expected the first place to be in Kensington, the Philadelphia community with the maximum overdose deaths, and where it had been arguing with neighbors about such a site. many months (with varying degrees of success) before the court’s decision. Residents south of Philadelphia also wondered: it was the first time many of them had heard of the site in their neighborhood.

Neighbors took to the streets to protest what they were saying an opaque process, without network participation The owner of the area where the site would be located, at Constitution Health Plaza, on the corner of Broad Street and Snyder Avenue, withdrew from the convention and Safehouse canceled its plans.

Previously, City Council member David Oh filed an invoice among his outraged colleagues banning such sites in Philadelphia.

Then Philadelphia City Council member David Oh introduced a law that would classify all supervised injection sites as health-destructive, requiring at least 80% network approval, making them virtually open. This invoice has not yet been voted through the City Council.

Meanwhile, federal prosecutor McSwain had requested a remaining lower court ruling pending his appeal. This appeal allowed.

Overdoses have killed an average of 3 other people a day in Philadelphia in 2019. According to initial knowledge from the Department of Public Health, overdose deaths were roughly the same as the city house maintenance order that at the same time last year. deaths are highest among Blacks in Philadelphia, as are the number of calls to the overdose-related medical emergency department.

Nationally, comprehensive knowledge should not be had to determine the full extent of the pandemic that has an effect on overdose deaths, however, an Associated Press investigation from nine states where it was known showed that overdose deaths exceeded their rates in the same period. months of last year.

The WHYY News Daily loose newsletter delivers the most local stories in your inbox.

The question of whether the Philadelphia-based nonprofit can open a supervised injection comes down to the drafting of the U. S. Controlled Substances Act. But it’s not the first time

Safehouse organizers said they plan to open it next week and will offer 4 hours a day.

A judge’s ruling that opening a position in which others can simply use illicit drugs under medical supervision would not violate federal law may set a national precedent.

Do you want a summary of WHY programs, occasions and stories?Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Together, we can achieve one hundred percent of WHYY’s training goal

WHY you connect it to your network and the world through providing engaging and reliable entertainment.

© WHY 2020

WHY it’s in partnership with