Lately we are in beta and we update it regularly. We would love to hear your feedback here.

Lately we are in beta and we have updated this research. We’d like to hear it here.

The advent of new techniques and materials, as well as inventions in interior plumbing systems, the result of the commercial revolution, paved the way for vertical life. this article reviews the evolution of the space plan in Europe between 1760 and 1939.

Addressing the transformation from housing to the commercial revolution to the interwar period, this segment highlights 4 striking examples that have redesigned classic advances and responded to the demanding situations of its time. 21st century urban fabric. Located in London, Paris, Amsterdam and Moscow, the plans provide ever-changing criteria for internal well-being, directly connected to a wider, matching and expectant urban population. Townhouses in the Garden Cities of England; Islote Haussmanniano, a vertical life for a fashion bourgeoisie; The extension of Amsterdam, from houses with alcoba to blocks of social housing; and the kind of transition house in Russia.

21

Back to Back Houses in Gardens Cities of England

As the trade revolution brought a large number of people to cities and an increasing number of lower-class workers, more types of housing were created. While some of these homes of the early 19th century developed organically, others were active government and charitable efforts to allocate the developing number of poor people that are being implemented.

On the one hand, the rich had moved into multi-story townhouses, boasting high ceilings and opulent eclectic-style ornaments; on the other hand, staff are squatted and take over abandoned houses, penthouses or are part of parish dwellings created through the church or personal projects through work homes.

But one of the most popular types of housing was townhouses in the commercial cities of Midland and northern England. The row of adjacent houses (2 to 3 stories) advised an incredibly small interior style with undeniable stacked rooms. less than 15 square meters, they would normally have the kitchen and bathrooms on the ground floor and one or two bedrooms on the first floor, sometimes they could even have a small attic and a backyard, however, they did not have enough openings or windows. , with a single visual facade and “shops”. Subsidized homes may have housed several families in one home. While these homes were built alongside industries through the staff themselves, many legislative attempts were made to ban their structure and were in spite of everything prohibited in 1909.

The Garden Cities style was then proposed as a solution imaginable from the 1890s, providing a more unique, personal and global lifestyle. In the grassy suburb of Hampstead, for example, special attention has been paid to the creation of a network and neighborhood. atmosphere between well-placed cabins, originally designed to combine all social classes. They were thought to be ideal communities. The opening between the internal and the external through personal gardens and panoramic perspectives was an additional attention that would bring comfort to the locals. .

Haussmann’s block: a vertical life for a bourgeoisie

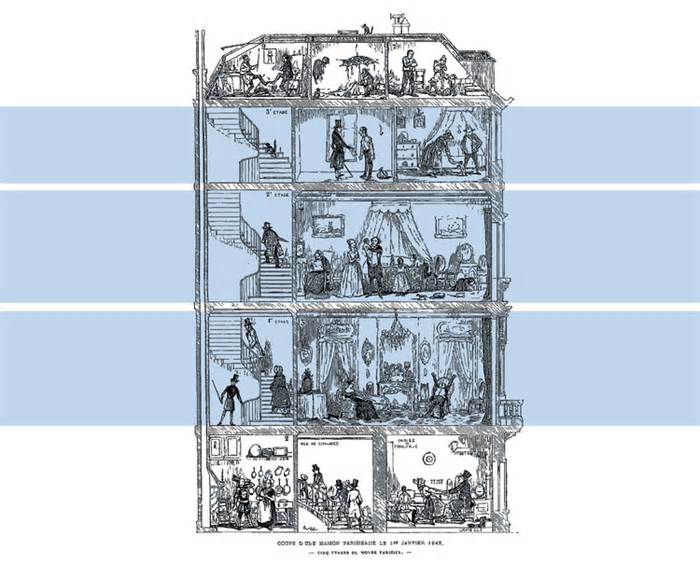

Paris, the world’s largest commercial city in the mid-19th century, had noticed that its population doubled; between 1853 and 1882, it became a Haussmannian city for the bourgeois fashion society. Modernization, sanitation and situations of life and infrastructure, this transformation has created not only, but essentially, an express spatial model, derived from the logic of the bourgeoisie.

The star-shaped grids of Haussmann’s networks generated specific triangular but also oblong blocks. Divided into plots, the block resembled a single building, basically due to the mixture of the same elements. source of ventilation and lighting. In the same building, there is no mix of the bourgeoisie’s living room and manufacturing position. In fact, “in the city of Haussmann, the office excluded from the personal residential block”.

According to the urban forms e-book, the death and life of the urban islet, in the Haussmannian transformation “the series of internal spaces had been reduced, but there was still a minimum hierarchy of put”. The apartments were regularly furnished facing the street and were directly available in the lobby. The back of the plot, due to geometry, allowed for less planned units, without dual orientation.

Supporting the emergence of a new civil society, each construction would bring together under one roof several families of other social classes. The second floor overlooked a balcony and was reserved for the richest families. destined for the small bourgeoisie, while the fifth was reserved for the lower classes, having a smaller balcony, for aesthetic reasons. The most sensitive floor, the “good room” was for the servants, with smaller rooms and shared bathrooms. It had direct access to the kitchens of the construction of the apartment, from a service ladder; On the other hand, on the interior side, each apartment had a giant antechamber leading to a hall that serves adjacent rooms on the facade: dining room, living room, bedrooms and reception, while the bathrooms were located on the side of the inner courtyard.

The extension of Amsterdam: from houses with alcoba to social buildings

From 1850 to 1920, Amsterdam’s population grew almost 3 times, the city did not increase in size. The modernization of the city began well when the North Sea Canal was executed and Kalf established the extension plan of 1875. In line with development, a transparent contrast was established between the bourgeois and working-class neighborhoods, in particular with the advent of “alcoba dwellings” or very small houses of 20 square meters, a room according to the family, with bed cabins in the kitchen. In some cases, the need for intensification led to excessive measures, in others all the space for the house was used, adding attics and basements. At the end of the nineteenth century, a new type of multi-storey structure was created, offering all the comforts. existing functions: housing, industry and merchandise garage, industry and small industry. Without paying attention to living conditions, the revolutiebouw or phenomenon of revolutionary structure was born.

Michel de Klerk, the long-term principal of the Amsterdam school, began to reflect at the time on the crisis and drew up plans for a social housing bloc. A transparent typological innovation, in the 1913-1921 era, the block no longer designed as an interchangeable unit, but evolved into a more complex organization, ensuring the continuity of the fabric and allowing the integration of other purposes such as housing, commerce and infrastructure in order to generate varied areas. , the backyards occupied the full intensity of the plot. The block had an interior space used in conjunction with its exits to the street by porches.

“Driven by the preference to supply individual housing to all circles of working-class relatives, the dwellings reproduce to the extent imaginable the characteristics of classic Dutch space with land directly open to the street, a small lawn at the back and a room on the first floor,” according to the Urban Forms ebook, the death and life of the urban block. The center generated rear personal spaces for the ground floor house, which together formed a courtyard, available from the street through a controlled passageway The street facade refers to the urban quality of the architecture, the narrow alternating protrusions corresponded to the stairs and kitchens, while the wide windows corresponded to the balconies; In addition, the historically open-room was indicated by a larger bay than the other rooms.

Finally, Amsterdam’s progression was based on the principles of mass housing. Modern and progressive, the extension of the city, made between 1913 and 1934, did not challenge the existing urban fabric, but experimented on the urban islet provided, exploring the living cells and its combination.

Transitional type space in Russia

The Narkomfin, built between 1928 and 1930 through the architect and prominent Soviet constructivism theorist Moisei Ginzburg, is a transitional building, an attempt to turn the individual into a housing network. It featured a popular, comfortable, well-designed and planned lifestyle. typical rooms and abundant soft grass through the continuous tape windows.

However, not all rooms had personal amenities and were intended for rehearsal only. The rest of the family purposes were in maximum cases shared and distributed in the five-story building, this included bathrooms, kitchen and other non-unusual regions. Well-structured and orderly composition, offering abundant area for network configuration and convenient flow to encourage interactions between guests. All regions are delimited through the structural poles of the grid.

Although this experimental style may seem horny to today’s users, it lacked the detail of confidentiality and was criticized for strict situations and disputes related to the use of regular spaces.

This article is a component of the subject ArchDaily: Inner Welfare. Every month, we explore an in-depth topic through articles, interviews, news and projects. Learn more about our monthly subjects. As always, at ArchDaily we appreciate the contributions of our readers; If you would like to submit an item or project, please contact us.

Now you’ll get updates on what’s next! Customize your feed and start tracking your favorite authors, offices, and users.

If you did all this and still can’t locate the email