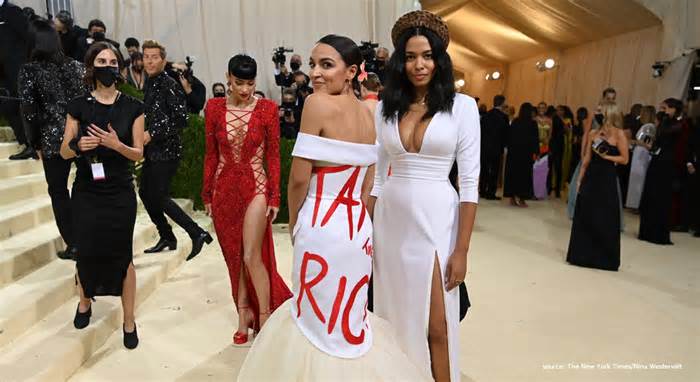

At the 2021 Met Gala, Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez sparked controversy and birthday party after dressing in a suit adorned with red graffiti with the “Tax the Rich” statement. To raise funds (for which tickets cost tens of thousands of dollars), the left-wing politician wore a traditional dress with the Brother Vellies fashion logo and also brought in the brand’s founder, young black designer and activist Aurora James.

Using fashion as a tool to deal with broader social considerations has long been a strategy for other people looking to make changes, adding dresses with those garments in spaces of influence.

From nineteenth-century suffragettes who roamed the streets in heels, ultra-feminine dresses in giant “photo” dresses and caps to refute claims they were not feminine, to patriotic textiles during World War II, to Indigenous Australian apparel and street accessories with a logo like this. Like Dizzy Couture today, the dress has conveyed political messages, creating “looks” for generations of replacement agents.

Here are five acts of disguising themselves as provocations that replaced history.

The founders of the American Revolution sought to break with the old codes of the European aristocracy. Much of the global still had “laptuary laws”: legal decrees that regulated the types, materials, and quantities of fabrics, colors, jewelry, and accessories. allowed to social groups.

In North America, the formal dress codes of the old regime were actively combated: men were not meant to wear the expensive and colorful embroidered silks worn in European courts; its imported fabrics were thought to be bad for local economies and its elite seemed to be in disspair. it contradicts the concept that all men can be (relatively) equal now.

President-elect George Washington sculpted through Houdon in the eighteenth century with a button missing from his vest. It is a gesture planned to show that his movements were more vital than his appearance. She also used a smooth sheet of woven American wool at home. for its inauguration instead of the expected silk or velvet. It’s a business demonstration of North American independence and perhaps the first American “business casual. “

Also read: Ruang (Ny) love: The dark side of the fashion industry and how to be a conscious consumer

Since the last eighteenth century, there has been a diversity of articles ranging from jewelry to dishes published to criticize the slave trade.

British Quakers had advocated abolition in 1783. the Abolitionist Movement.

The silk cord bags, made in sewing circles, were brought to personalities such as George IV and Princess Victoria. The bags contained newspaper articles and pamphlets in favor of abolition.

The Abolition of Slavery Act, which provided for the early abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire, was passed ten years later, in 1833, a similar law not ratified in the United States until 1865.

The ostrich and exotic bird industry was large in the nineteenth century: in addition to feathers, women used whole bodies of birds as accessories, such as hummingbird earrings.

The “double fluff” ostrich feather industry was centered in South Africa, where feathers were worth more than gold. They were exported to cinemas in London and New York, where exhausted women finished them and dyed them for retail sale.

In 1914, a “massive collapse” made raw curtains almost useless. Young women interested in the development of the national park and conservation movements have opposed the industry on ecological grounds. They simply stopped dressing fashionably, starting a global “anti-plumage” movement. .

The women involved in the Massachusetts Audubon Society were so successful that their lobbying led to the first U. S. federal conservation legislation. The Lacey Act (1900). Birds with taxidermy, feathered boas and birds as earrings have been largely obsolete and rarely used. noticed in women’s fashion.

The AIDS crisis of the ’80s and ’90s saw the mobilization of an exclusive mix of activism born out of the feminist, Hispanic, black, and gay movements of the ’70s. ACT UP New York decided that only civil anger and disobedience would draw the attention of government and big pharma to the plight of the most commonly physical care of gay men.

A series of ordinary “zaps” or site-specific, theatrical events were conceived. ACT UP members included qualified personalities from advertising and design who created unified and sublime t-shirts, posters and banners. The designs were clean, elegant and looked like elegant advertising.

As Sarah Schulman recently demonstrated in her 20-year ACT UP history, ambitious T-shirt designs have created an optimal effect on ACT UP TV news protests and a new pro-gay identity. Jackets, clean, tight jeans or denim shorts, ACT UP has set the gaze of gay urban men for a generation.

Government agencies and Big Pharma have been humiliated through public outskirts to adopt larger, more rational fitness messages, conduct fairer and more funded drug trials, and sell less expensive retrovirals.

In 1984, designer Katharine Hamnett wore a T-shirt that read “58% OF THOSE WHO WANT PERSHING” (a reference to nuclear missiles) in a high-profile fashion attended by Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Hamnett made his jersey the day before, seeing the opportunity he had, and hid it in his coat at the entrance. Its graphic format is due to the Punk of the 1970s and ACT UP. He later recalled the widely photographed encounter with Thatcher:

She looked down and said, “It seems that you carry a pretty strong message on your t-shirt,” then leaned over to read it and let out a scream, like a chicken.

Also read: What Indonesia’s future leaders can learn from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

Social replacement desires its visual forms. Fashion is one of them. Fashion is a brilliant communicator of new ideas. What we read about AOC’s clothing “controversy” proves that she fully understands the strength of fashion.

This article was first published on The Conversation, a global media resource that provides cutting-edge concepts and others who know what they’re talking about.