Twenty -two years before betting on his corporate in Bitcoin, the CEO of Microstrategy, Michael Saylor, sat for a long interview with Forbes that invoked Martin Luther King, Mama Teresa, Churchill, Caesar and Lincoln. At that time, in 1998, the company was a favorite of Wall Street, thanks to its DOT-COM Software Suite. Microstrategy had only $ one hundred million in sales, but Saylor thought about how a day when his generation would be used through “all on the planet. ” He was 33 years old and may not see the accident of March 2000 to arrive or that the inventory of microstrams languished for two decades.

Of Forbes, September 7, 1998:

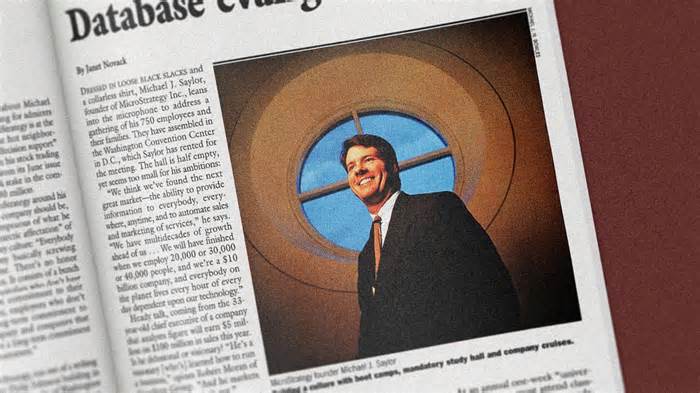

Michael Saylor of Microstrategy is a visit or an egotist delusional. Anyway, giant consumers are aligning to buy their software.

Dressed in funky black pants and a shirt without a collar, Michael J. Saylor, founder of Microstrategy Inc. , looks at the microphone for rally techniques from his 750 workers and their families. They met at the Washington Convention Center in D. C. , which Saylor praised for the meeting. The room is partly empty, but it is too small for his ambitions:

“We think we’ve found the next great market — the ability to provide information to everybody, everywhere, anytime, and to automate sales and marketing of services,” he says. “We have multidecades of growth ahead of us . . . We will have finished when we employ 20,000 or 30,000 or 40,000 people, and we’re a $ 10 billion company, and everybody on the planet lives every hour of every day dependent upon our technology.”

Heary Talk, coming from the 33-year-old CEO of a company that, analysts say, will earn $5 million from $100 million in sales this year. Is he delusional or visionary?” He’s a visionary [who] learned how to run a business,” said Robert Moran of the Aberdeen Group. “And he markets what he has. “

Say what you will about Michael Saylor, there’s no shortage of him for Wall Street fans. Microstrategy is at the intersection of a few red-light districts: the web, “decision support,” and databases. With his shares at $39, up 225% from his June factor price, Saylor’s 64% stake in the company is worth $880 million.

Loving the mooring of microstrategia around his vision of what a business is, Saylor is derogatory of what he considers as “the Antarctic task” of Silicon Valley’s culture: “Everyone [there] are kissing everyone. ” They have no long -term commitment to their companies and their corporations that have no long -term commitment to their clients.

MicroStrategy, Philip Johnson’s short 17, in the Virginie suburbs of Washington D. C. , isn’t a position that brings your dog to work. New hires, even seasoned executives, will have to take a six-week “boot camp” and take tests on the company’s software and marketing message. During an annual week-long “college,” all workers will have to take courses from 8 a. m. to 6 p. m. , with a mandatory exam room starting at 8 p. m. At 10 p. m. , Saylor takes all the workers on an ocean cruise, with no spouse invited. “Our culture is part intellectual, part military, part fraternity, part religion,” Saylor explains.

Saylor is in the information sorting and extraction business. Retailers, banks and other companies have been spending big bucks to build data warehouses containing masses of information about individual customers and transactions. Then 50 or 100 folks sit at headquarters and use a query engine and tools — sold by MicroStrategy or its competitors — to try to extract insights from these huge databases.

The retail Best Buy analyzed what products that consumers buy in combination: CD buyers tend to load in the film, for example, to help it reconsider its store design. Petsmart uses its warehouse to adapt the variety of actions for individual markets; Dog sweaters are now stored in larger sizes in rural areas.

In 1996, Microstrategy launched its first product that allowed users to challenge a database on the web or an intranet without special desktop software.

Now MicroStrategy has just rolled out “DSS Broadcaster” — a “push technology” product. Preset queries are run against the data warehouse. Users can either receive all reports or an alert — by E-mail or fax or pager — only when there’s an unexpected result. For instance, Spain’s La Caixa savings bank may use Broadcaster to reach all 4,000 branches with alarms about nonperforming loans or with prospect lists for some new marketing push.

Saber Group, which sets aside $66 billion in year-consistent bookings, is also a MicroStrategy client. It has just built a warehouse of airline reservations (2,000 gigathroughtes) that will go to four teraoctets when hotel and rental car reservations are added. About 1,000 Saber workers will, in all likelihood, have access to at least some of the data, as will airlines that will now buy sabre reservation data strips, explains Kathleen Wayton, director of the warehouse. In addition, in the coming years, employing the diffuser, Saber plans to sell reports via email to agents and corporations that want more correction on their expenses. A company can also buy Internet access to extract data, such as reserved facilities, a higher number of prices from the last minutes.

Saylor also sees a customer market for warehouse data. An example: an individual bank visitor can log in to get an alert if your balance has become too low. And Saylor predicts that the data made on customer purchase behavior, combined with the Push generation, such as diffuser, will significantly expand direct sale.

“We will use our generation to erase the total source chains, to move the way other people buy,” he said. It remains to be noted if consumers need to be bombarded and bombarded with alerts and land.

“We’re playing for all the marbles, to essentially win the entire industry, worldwide, forever,” says Saylor grandly. Wait a minute. Aren’t bigger companies — including Oracle and Microsoft — after the same marbles? Yes, but for now MicroStrategy’s tools (which can run on an Oracle database) allow more detailed analysis of big databases.

Other small companies in this market, eyeing the competition, have been merging or selling out. Saylor is contemptuous of that. More of his Silicon Valley thing: “It’s get rich quick. Don’t think about tomorrow. Go fast. Die young.”

Saylor has sold any inventory in MicroStrategy’s initial offering. But he and other insiders took a $10 million dividend before the offering. In addition, the audience consistent with participants in the center will download only one vote through the action, as opposed to ten consistent with Centege for initiates. He opts for all the balls, but counts his votes.

The son of an unleashed Air Force officer, Saylor, grew devouring history books and is obsessed with the heroes and fans bigger than life. In a long interview, he invoked Martin Luther King, mother Teresa, Churchill, César and Lincoln. When he enrolled in the MIT in a Rotc scholarship, he was surrounded by another validitor of the best school that was as bright as he. He concluded there that the “basic differentiator” is: “How much do you need?”

Saylor carries this competitive intensity in all areas of his life. Here’s his description of the infrequent seven-day vacation in London: “I saw five musicals, a royal philharmonic, a Shakespeare, 1Five Museums, and 7 castles. “

Saylor planned to be an Air Force fighter pilot and astronaut. But before he graduated from MIT, he says, an Army Corps proved he had a central whisper, disqualifying him.

So he ended up in New York, working for a struggling computer consulting firm, writing computer simulation models for DuPont. When his bosses demanded he sign an agreement not to compete, he did the opposite. He called DuPont and offered his services as an employee.

At 24, he told Dupont that he prefers to be an independent consultant. Dupont gave him an area and contract of $ 250,000. Equally important, Saylor talked about the fraternity of the MIT, Brother Sanju K. Bansal, an engineer born in India with a master’s degree in PC Science, leaving Boaz, Allen joined him in the new company.

Bansal, 32, is chief operating officer and has a 14% stake in MicroStrategy, worth $195 million. The soft-spoken Bansal smooths ruffled feathers when the zealot Saylor goes too far. Still, Saylor’s aggressive style sets the tone. At trade shows in 1993, MicroStrategy cranked up its sound system so loud that better-known exhibitors, with more salesmen, couldn’t make their pitches.

Saylor does not apologize for his great ambitions. “There is nothing more frustrating than seeing the cynics there and saying:” Well, nobody can gain more effective because Microsoft and Intel have everything, “he smokes. “Is the software industry mature or embryonic? I would say it is embryonic. There will be one hundred additional Microsoft, not just one. “

More Forbes